Welcome back to Living Abroad, a series that shows you what it’s like to live as an expat in cities around the world. Today, we’re chatting with Rika, a Canadian English teacher who just spent three years living in Japan.

Here, Rika discusses the pros and cons of living in Japan, from the delicious food to the stigma of living as a foreigner in Japan. I’ve followed Rika for years (way back when she lived in Honduras!) so I’m very excited to share this interview today.

Quick facts about living in Japan:

- Language: Japanese

- Currency: ¥ Japanese Yen (JPY)

- Level of crime in Japan: Very Low

Cost of living in Japan: Moderate

Quality of life in Japan: Very High

The pros and cons of living in Japan:

- Pros: extremely safe, delicious cheap food, great public transportation

- Cons: a very high language barrier, technology is still in 1995, lack of AC in summer

The expat community in Japan:

- Size of the expat community in Japan: 2.6 million foreign residents in 2018 (source)

- Most common expat nationalities: Chinese, Vietnamese, and South Korean. Eight out of the top 10 home countries of foreign residents are other Asian countries! Brazil is #5 and the USA is #8. (source)

SONY DSC

SONY DSC

Rika’s background:

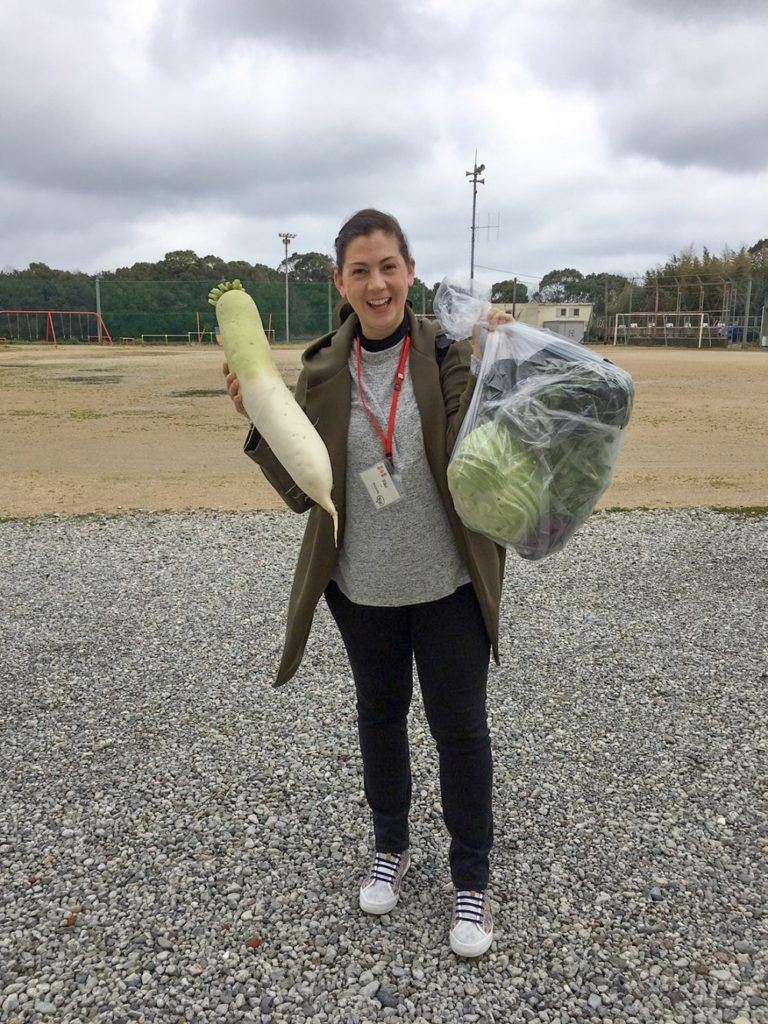

Hi! I’m Rika and I’m originally from Canada. I work as an ALT (Assistant Language Teacher) in Japan, and I’ve lived here since August 2016. My town is called Naruto (yes, like the anime) and is on the island of Shikoku, the smallest of the four main islands that make up Japan.

I came to Japan on the JET Programme, which is a program that brings native English speakers from around the world to Japan. Our job is to assist Japanese teachers with their English lessons in the public school system. That’s a bit of a fancy way to say that I’m mostly a human tape recorder and a dancing English monkey for most of my workday.

On the weather in Japan: Japan is a country that runs almost north to south, from the northernmost tip being up by Russia and the southernmost tip being down near Taiwan. This means the country experiences a wide variety of weather. In my area – I’m in south-central(ish) Japan – we do get the extreme Japanese summer, with temperatures of 40°C (104°F) for months on end with 90-100% humidity. But our spring, fall, and winters are all very mild. It rarely snows for more than a day each year where I live, and as a Canadian I’m very, very happy about that.

On Japan’s famous seasons: The seasons here are distinct and lovely. Spring brings cherry blossoms, fall brings brilliant red leaves, summer brings hydrangeas and lush greenery, and winter is a time to rest and reset. Japanese people will proudly tell you that “Japan has four seasons” like no other country in the world has that. (It’s so prevalent that it often makes its way into Japan memes.) I now understand what they mean… they have four seasons AND each season is celebrated to the max, with special foods, festivals, and rituals for each season. Nobody enjoys a season the way Japanese people do!

On learning Japanese: Japanese is an easy language to learn the bare-bones basics of. But after that, you quickly realize there is a steep learning curve.

I feel quite comfortable with spoken Japanese – I can get my point across and I understand what people are saying to me. But written Japanese is difficult. They use three different writing systems (all mixed into the same sentence) and one of them is Chinese characters, of which there are literally thousands and many look alike.

Japanese people are generally very shy about speaking English, so if you try to speak Japanese to them they will often be relieved and jump right into it with you. However, many of them have had limited interaction in Japanese with non-native speakers, so they are not used to slowing down or enunciating their speech. Learning how to say “slowly, please” was a great first step for me! (“Yukkuri de, onegashimasu!”)

On the level of English in Japan: Overall, I’d say about 98% of people where I live do not speak English beyond “Hello” and “What’s your name?”. I live in what’s considered to be a very “countryside” prefecture, in a small town (by Japanese standards – there are 60,000 people here). There is very little interest or motivation for people here to learn English.

There’s also little to no tourism from English-speaking countries, and people here generally do not need it for work or to go about their day to day lives. For example, there’s no English at the local bank for forms and apparently no one there can (or wants to) speak English. The ATM is all in Japanese. So is the online banking.

Yakibuta tamago meshi (fried pork belly and an egg on rice) in Imabari, Ehime

Yakibuta tamago meshi (fried pork belly and an egg on rice) in Imabari, Ehime

On the food in Japan: Each place in Japan boasts its own local specialty. The best one I’ve had so far has been yakibuta tamago meshi (fried pork belly and an egg on rice) in Imabari, Ehime. It doesn’t look like much, but it tasted spectacular!

My favorite Japanese food is ramen, and I was on a quest to try one from every prefecture! Sadly I was diagnosed with an autoimmune disease a couple of years ago here, and have had to transition to a gluten-free diet, so ramen is off the table.

I also love sushi and I end up going out for sushi at least once a week. I live within a 20-minute drive of three conveyor belt sushi places, and the great thing about those here is they’re $1/plate.

Butter corn ramen in Hokkaido

Butter corn ramen in Hokkaido

On adjusting to Japanese culture: The shoganai is what I most loathe about Japanese society. Shoganai means “it can’t be helped” and it took me a very long time to get used to people throwing that out as a final answer for THINGS THAT COULD DEFINITELY BE HELPED. When I asked for a change, I was often met with this answer.

Living in Japan means you need to be able to “read the air”, meaning you need to pick up on subtleties and unspoken rules to keep the group harmony. It’s kind of a combination of “don’t stir the pot” and “read the room”.

On safety in Japan: This is absolutely, without a doubt, the safest place I have ever lived or visited. I don’t need to lock my doors, I can leave my iPhone on the table at Starbucks to save my seat. If I drop my wallet, I’ll likely find it at the closest police station with everything in it.

That being said, my prefecture has some of the worst drivers in the country and I do not feel safe driving here. People often watch TV on their in-car entertainment system and a lot of the rules of the road are not followed. Streets are extremely narrow and not well-lit. This also makes me nervous when walking on the sides of roads.

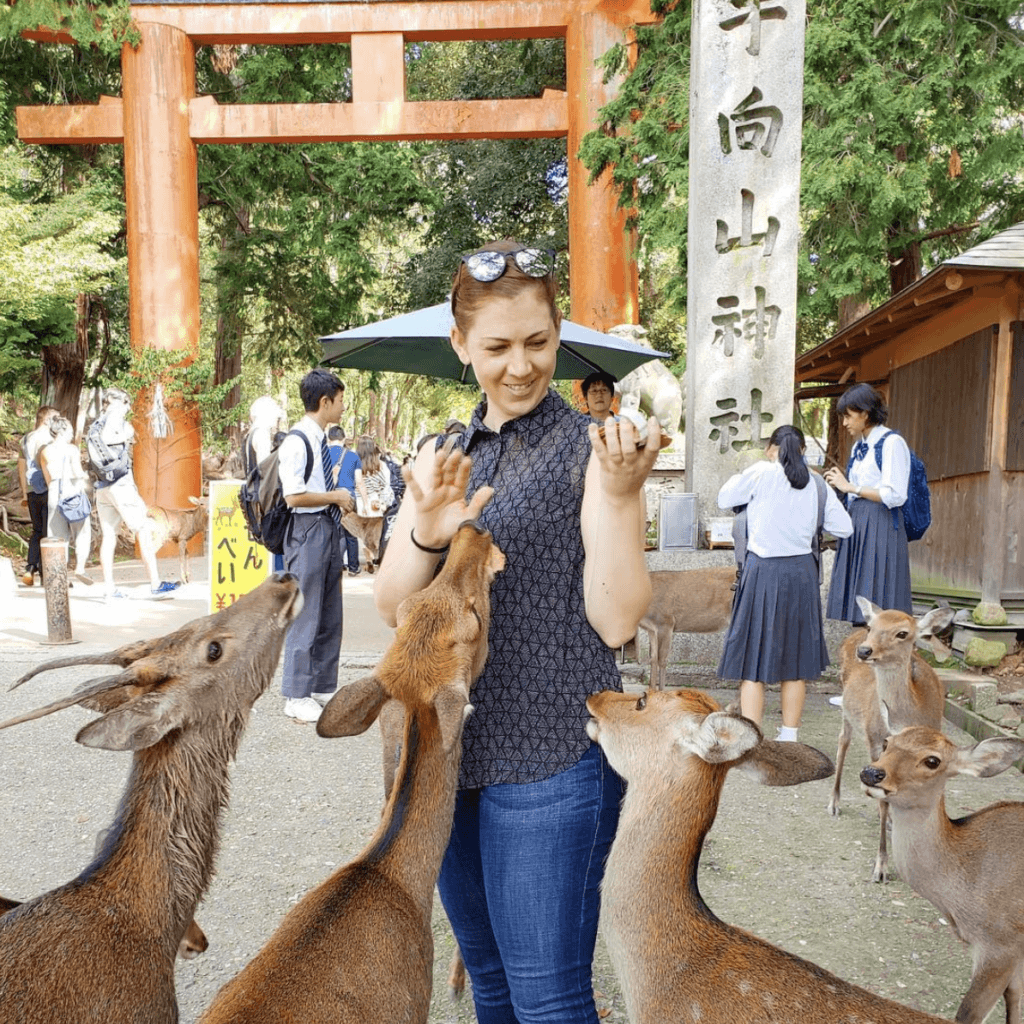

Nara Park in Nara, Japan

Nara Park in Nara, Japan

On getting around Japan: Most of Japan is well-connected with all kinds of transit. The trains are extremely punctual. One thing to keep in mind is even in metro areas, trains stop running between midnight and 1 am and don’t start again until around 5 am. Don’t miss the last train!

On traveling solo in Japan as a woman: As a solo female traveller, I couldn’t ask for a safer, more comfortable place to travel alone. From road trips to plane rides to never-ending trains to catching local buses, traveling here is a dream. Speaking Japanese does help, but overall people are very kind and eager to learn about you and what you’re doing.

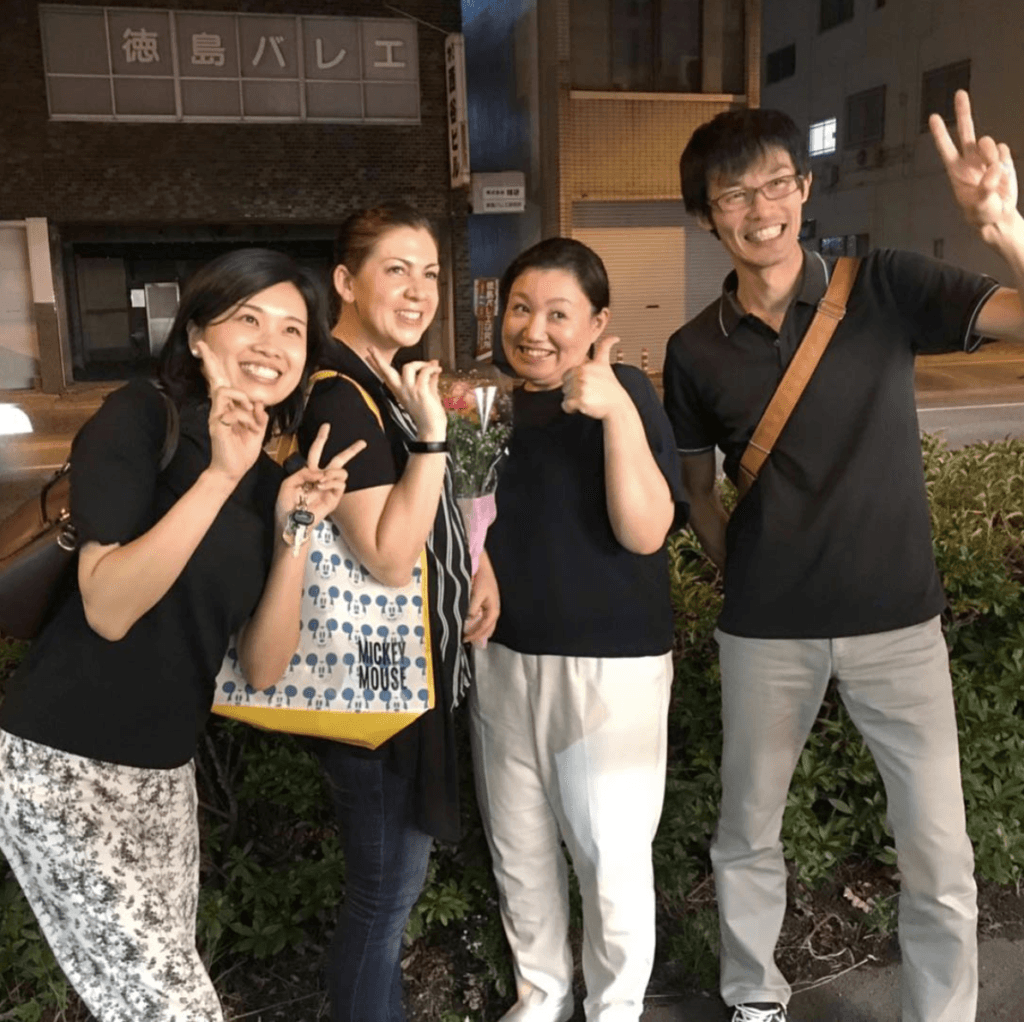

On making friends: I initially made friends through my job, as I met many English teachers in my town and surrounding area. I also made friends with a lot of the ALTs who came out of the same consulate as me in Canada (we all did training together and flew to Japan together). I have a lot of teacher friends!

My best circle of friends here came from joining a local traditional dance team. My prefecture, Tokushima, is famous for Awa Odori which is the largest dance festival in Japan. I just finished my second year dancing at the festival, and the people on my dance team have become my Japanese family. They are lovely people and some of the best friends I have made here. Here’s a video of the dance.

On the cost of living in Japan: The cost of living is fairly normal for a first-world country; I pay about the same as in small Canadian towns. Rent is a bit cheaper in my town, but that’s because where I live is considered the middle of nowhere in Japan. My rent is subsidized, but for a similar style of apartment (ie. a one-bedroom style) you could expect to pay $400-600 USD a month, excluding utilities, for a new-ish apartment. One thing to note here is that appliances are generally not included in apartment rentals – you have to buy your own.

On Japanese healthcare: Japan operates a National Health System (NHS). Residents pay into it every month in the form of a deduction on each paycheck. Then, when you use the system, you are responsible for 30% of the total cost. The NHS covers both medical and dental care.

One thing I like about the NHS is there’s no referral system. If I want to see a specialist, I call them and make an appointment myself (unlike in Canada). There’s no waiting four months to get an appointment here. Also, I can choose my doctors.

The only downside is having to pay for the NHS twice – once through a deduction on my paycheck, then also having to still pay 30% every time I use the system. That being said, paying 30% of the appointment cost is not a huge amount. For example, I see an endocrinologist every six months where I get a blood test, consultation with the doctor, and an ultrasound. This sets me back a whopping $40. A teeth cleaning costs around $15.

Overall, the health care here is like any first world country and there is a high level of care. However, many expats express frustration with the system here, especially if you are a woman. Symptoms can often be brushed off by (old male) doctors who will tell you to “just relax” or “don’t be so stressed”. You definitely have to be able to advocate for yourself here. Mental illness is still highly stigmatized and often just swept under the rug.

Fushimi Inari Shrine in Sapporo, Japan

Fushimi Inari Shrine in Sapporo, Japan

On the technology: Everyone thinks Japan is this futuristic robot high-tech place but let me tell you, that’s one neighborhood in Tokyo and that’s about it. People are still using fax machines for everything here. The office administrator at my school doesn’t know how to attach files to emails. The IT guy at my board of education doesn’t know how an internet router works. There’s no internet on any of the smartboards in my classroom. The only restaurants with wifi are McDonald’s and Starbucks. Don’t even get me started on the ATMs that CLOSE AT NIGHT AND ON WEEKENDS and the “online banking” that deserves those quotation marks.

On holidays in Japan: Christmas is a pretty funny holiday in Japan. It’s a day for going on a date, or eating KFC with your family. Yes, KFC. They sell specific Christmas buckets and you have to order months in advance, and they usually sell out!

But as for a truly Japanese holiday, Setsubun is a quirky one. It’s held every February 3rd, and is a festival celebrating the beginning of spring in Japan (for most of the country, spring is from around mid-February through the end of April). It used to be sort of a New Year’s festival back when Japan was still following the lunar calendar.

Locals celebrate Setsubun by having the oldest male or head of household wear an oni (ogre) mask and the rest of the family members throw roasted soybeans at the oni and yell “demons out, luck in!” and chase the oni out of the house and slam the door. Some people still do this at home (especially if they have kids, as kids love chasing the oni) but these days most people go to a temple or shrine to celebrate.

Girl’s Day decorations in Tokushima

Girl’s Day decorations in Tokushima

On what she misses from home: Sometimes I miss just the ease of going into a restaurant and being able to read the entire menu easily or ask questions. Restaurants here are not really down with substitutions and as someone with a lot of food restrictions, that gets frustrating sometimes.

I also miss the variety of food. I love Japanese food and honestly am happy eating it every day, but I don’t have much choice outside of it. If I want Vietnamese, Ethiopian, or Greek food I’m out of luck. My town has one Indian restaurant and some Japanese-style western restaurants, and that’s it for non-Japanese stuff.

On what she wishes she had brought from home: PANTS. PANTS ALL DAY LONG.

I am 5’8” and usually wear a size 12 or 14 pant in North America. That’s a 5XL (!!!) in Japanese pant sizes, and sizes above XL (around a 6-8 US) are often only sold in specialty stores in larger urban centers or online. I am also much taller than most Japanese women, so even finding the right size of pants were way too short on me. Also, the Asian body type for most women here does not include curves or any junk in the trunk, so pants here really don’t accommodate that at all. Pants here are my enemy. I should have brought more. Now I order American brands off Amazon!

On living in Japan long-term: I wouldn’t consider living in Japan long-term. While I love this country and I’m grateful for the opportunity I’ve been given to live here for a few years, the unwillingness to integrate foreigners into their society is a red flag for me. You could live here for 50 years, speak fluent Japanese, do everything right culturally and still get the “OMG A FOREIGNER” yells and pointing while you do your grocery shopping, and people will still ask you if you know how to use chopsticks and when you’re going back to your own country. I can’t get down with that. But it’s a great place to spend a few years and get to know the country on a deeper level than just being a tourist.

Thanks so much, Rika!

P.S. What Living as an Expat in Shanghai is Really Like and What Living as an Expat in Singapore is Really Like.